Friday was both the last day of 2021 and, for Katie and me, the last day of our fourteenth year of marriage.

Wait, that sounds weirdly ominous. All I mean is that it was our 14th wedding anniversary.1

One benefit of having gotten married on a holiday is that I’ll never be the victim of the tired sitcom trope “Dad Forgets Anniversary… Again,” wherein I draft the children, the dog, and — let’s say the FedEx guy — as accomplices in an unlikely and over-complicated plan to find the perfect last-minute gift all while giving my wife the impression that the present had been in place for months.

But because our holiday anniversary arrives in the wake of often-extended Christmas celebrations its observance is often relatively muted. Oh sure, we’ve been to several of the finest restaurants in western Saline and eastern Lafayette counties — free refills and everything — but it’s hard to escape the cognitive dissonance of celebrating another year of marriage only, at the end of the night, to retire with your spouse to your childhood bedroom.

This year, both Katie and I were sick (non-COVID), so we wished each other happy anniversary, blew our noses, and went to bed at 10:30.2

Early in her career, Joan Didion, who died in the last week of last year (which as of this writing is also last week), wrote3 “I enter a revolving door at twenty and come out a good deal older, and on a different street.” This line arrives at the end of a long sentence in which she gives her eight early years in New York — the bulk of her 20s — a self-consciously cinematic montage treatment.

But I’ve kept that last part of the sentence and its downbeat punchline with me in the 20+ years since I read it. It pops into my head whenever it hits me that something has fundamentally changed. With a soft airlock whumph, the door deposits me, stumbling and slightly bewildered, in a new phase of life. On a different street.

My first encounter with Didion’s essay came in ENGLISH 145, Paul Hendrickson’s popular class in Creative Nonfiction at Penn’s Kelly Writers House. I gained admittance to the class just a semester or two before PH achieved a certain cult-like status among a certain subset of us on campus. It is the most important class I’d ever taken, and at the time I would almost certainly have said it had profoundly changed my life.

But I was 21, and in college (barely), and all kinds of things were falling apart around me so I missed the actual profound life-changer, which also occurred that year (2000), just over two blocks away.

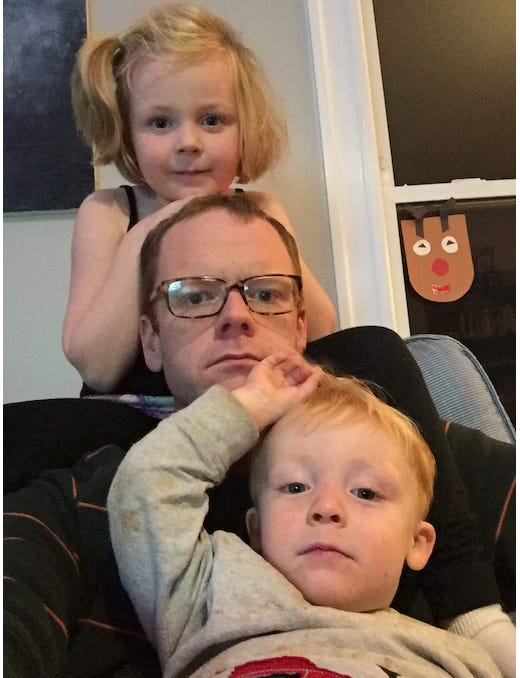

Stacy introduced us at The Daily Pennsylvanian offices. Stacy was an editor at The DP. I … was just always there. Katie had come in to say hi to her friend. For some reason I remember her as clad all in denim, and there’s some dispute as to whether or not this was actually the first time we met but, with the fuzzy-edged rom-com sheen offered by two decades’ worth of hindsight, I remember a beaming, full-cheeked smile that my heart sometimes leaps to see in the faces of (spoiler alert) our children.

Me? I probably had a piece of the newspaper’s ubiquitous bad pizza halfway to my mouth.

WHUMPH — Time’s revolving door dumps us on a West Philadelphia sidewalk another dozen blocks over. It’s 2003, and we’ve just had a lovely dinner at a nifty little Mexican restaurant as one of our early (second? third?) dates.

We had been talking about football (?!). I’d described my undistinguished high school career, which for reasons I can’t now fathom required me to demonstrate “proper tackling form.” Imagine Tom Cruise doing the sexy “here let me show how you to hold the cue stick” move except everything is the opposite. I placed my shoulder in her stomach, grabbed the back of one of her legs and … took her to the sidewalk. It was a perfectly legal, if ill-advised, tackle.

WHUMPH — I’m at my apartment in Delaware, preparing for her first disastrous visit (detailed here).

WHUMPH — On a couch in Concord, Mass., I’m watching soap operas with Katie’s mother. Katie’s moved home after her mom’s cancer diagnosis. I followed. Sometimes Mrs. Walker starts a cleaning project, runs out of steam, and allows me to try to earn my keep by completing it under her supervision. I’m unemployed, with few prospects. I live in the guest house.

WHUMPH — I’m looking for a job at Harvard, so that the cost of classes I’m taking at the Extension School will be nominal. At the interview for an office manager gig, my soon-to-be boss says “I would do anything for [Katie’s dad, her former boss].” I begin to appreciate the value of nepotism.

WHUMPH — We’re married, and now the revolving-door seems to spin more quickly even as more time has elapsed each ti—

WHUMPH — I’m in the elevator at Cambridge Hospital with a doctor who I swear to God looks like Jason Robards. I’m holding an infant car seat. It’s possible my palms are sweating and/or I’m visibly shaking.

ROBARDS: First one? ME: Yeah. ROBARDS: Nervous? ME: It doesn't seem like they should let us take her home. ROBARDS: With an attitude like that you'll be fine.

WHUMPH — I sit with fellow classmates at the Emerson College Commencement, blissfully unaware that Katie has spent two hours in the balcony wrestling with a grumpy, teething toddler. Afterwards, things seem fine!

\WHUMPH — And then there were two?

Since those we’ve changed our last diapers and the 12-year-old got braces which meant she’d lost her last tooth and for every revolving-door-marked flashbulb memory you realize (WHUMPH) there are a dozen more you’ve failed to note.

It’s enough to take your breath away.

“We couldn’t wait for 2008!” was the very-clever line on our save-the-date cards.

We had to stay up a little past our bedtime, it’s New Year’s Eve, after all.

This passage appears in “Goodbye to All That,” the anchoring essay in Didion’s first collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem (which seems to be on back-order!). NB: “Goodbye…” itself is sort of the ur-“Leaving New York” essay.

Loved it always knew you were lucky with Katie