Well, it’s over.

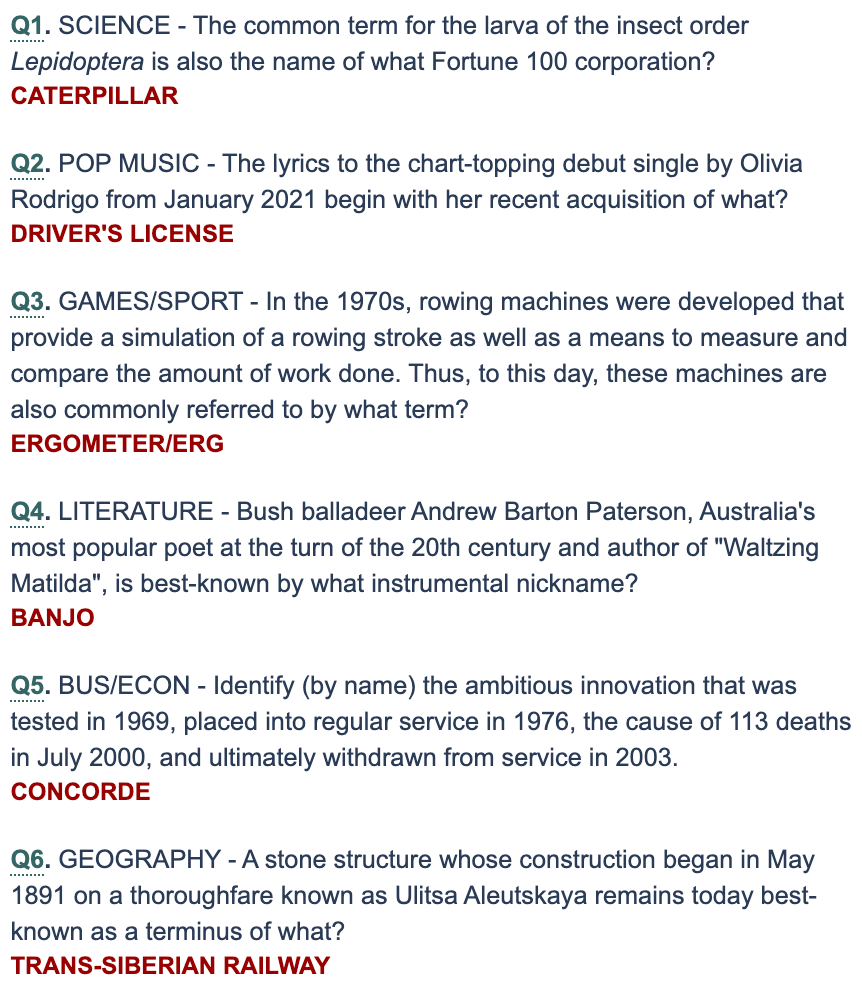

My first season of the trivia contest/pyramid scheme/possible cult indoctrination mechanism called LearnedLeague, is over. I finished 9th out of 34 in the rookie “Rundle” — this particular subculture’s term of art for its competitive groupings.

You can read more-detailed paeans to LearnedLeague here and here, but basically it’s a gathering of 30,000-some trivia freaks who are placed into dozens of divisions and tiers within those divisions and then face each other in one-on-one matches over the course of a five-week season.

It’s a little convoluted until you start playing, but the basics: you get six questions every weekday morning for five weeks. You answer them as best you can without availing yourself of any outside help (it’s all on the honor system, if you can believe it), and then you assign a certain number of points to each question, based on your reckon of how your opponent will fare with that day’s slate. This makes it entirely possible to answer fewer questions correctly and still come away with a win.

Any lingering skepticism about the overweening enthusiasm so many people seemed to have for the regrettably-named endeavor was banished on the first day of the season, when I answered all six questions correctly and found myself in first place.

At last, a true meritocracy! These folks must be on to something after all!

My reign atop the standings lasted two glorious days.1 One of the geeky features of this league is its tracking of statistics. So all future opponents will be able to see my record in question-answering broken down by subject, like so:

Back when I was obsessed with this stuff (and was also younger, with more energy, more free time, and fewer children), I might stare for hours at lists of previous Nobel Prize winners or U.S. Presidents, even though I know that’s not the best way for me to soak up this “knowledge.” The way I suss out answers to obscure trivia questions involves a web of free association and blind guesswork that draws on my years of soaking up various pieces of culture, high and (mostly) low.

I can’t, for instance, definitively place Millard Fillmore’s years in office (offhand I’m going to say the 1850s?)2, but the name sends me on associative leaps — first to a never-funny newspaper strip and then, to a primetime ABC show (it ran on, I want to say, Wednesday nights):

Head of the Class is a series about a group of gifted-but-uptight high schoolers at New York City’s fictional Millard Fillmore High. They fall under the sway of Howard Hesseman’s charismatic and laid back Mr. Moore, a history teacher determined to show them there’s more to life than getting the right answers.

My brain, in trivial free-association mode, will then note that of course Hesseman played Dr. Johnny Fever on WKRP in Cincinnati (which theme song I still know by heart). My brain further notes that the character who passed for a late-80s version of a computer geek was the heavyset Dennis, played by an actor named Dan Schneider, who would go on to first success and then infamy as the creepy, foot-loving Svengali behind several of Nickelodeon’s biggest shows. (The shows are bad, but, if my students are to be believed, they’ve shaped a generation).

Linger with me a bit longer here on this silly path: Head of the Class was my first exposure — a-way out there in the provinces — to Broadway musicals of any kind. Via the plays the gang put on, I got pretty good precis of “Little Shop of Horrors” and “Hair.” I’ve still never seen a proper production of either one (though I have seen the Rick Moranis movie), but I can answer lots of questions about them.

The show also introduced me to the concept of the Quiz Bowl aka Academic Bowl aka College Bowl, where two teams of high school students square off in, well, a trivia contest. Before I watched Jeopardy!, I watched Arvid help the Fillmore team pull out a win over rival Bronx Science (or, in a few very special episodes, their counterparts in Moscow). I remember, during those episodes, willing the portions devoted to the actual competition to go on indefinitely.

A Quiz Bowl competition (or Jeopardy! for that matter) has the air of an intellectual exercise, but the knowledge is mostly surface-level stuff. You didn’t have to know about, say, the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, only that it was signed in 1919 and it ended World War I. The ways in which its punitive attitude toward Germany may have helped fuel the resentments that led to Hitler’s ascent is a plausible you should not have taking up the space in your head that could be occupied by the knowledge that Ann B. Davis played Alice the housekeeper on The Brady Bunch. My erratic, broad-but-not-deep reading (and TV-watching) had allowed me to pile up an impressively shallow web of facts.

We started a Quiz Bowl team in high school my junior year. And, if you’ll forgive me a “Glory Days”-style reminiscence and brief bit of immodesty: I was good. There was something almost pre-verbal about the experience when things were going well. I’d let my eyes go out of focus and dredge up answers from wherever in my subconscious they were stashed. Key words lead to answers, if not understanding:

Desert Fox? —> Erwin Rommel

Swamp Fox? —> Francis Marion

Redd Foxx? —> Fred Sanford

Sanford and Son? —> a remake of the BBC’s Steptoe and Son

Family Matters? —> Spun off from Perfect Strangers

Mork and Mindy? —> Spun off from Happy Days, along with Laverne and Shirley and (of course) Joanie loves Chachi

This is where I mention that I made first-team all-state in 1997.

For the last two seasons, Hessemann was replaced by Scottish comedian Billy Connolly, about whom I remember very little except for this little bit of “one person’s terrorist is another person’s freedom fighter” clearly excerpted from his stand-up routine:

I know at least two subscribers to this email who would take issue with Connolly’s framing here (Hi, Seth), but his point that so much of life is a matter of perspective might be just what these geniuses who have spent six years in high school need.

It’s getting a little late for this post, so I’m going to cut to the epistemology. What is the correct answer to the following trivia question: “Who killed John F. Kennedy?”

Lee Harvey Oswald? Sam Giancana? Castro? FBI? CIA? LBJ?

And, lest you think I’m a nut, there are plenty of unanswered questions, summed up neatly in this thread from <checks watch> yesterday (thanks for the tip, Derek):

We can make the question definitively answerable if we prepend the clause “According to the Warren Commission’s report… .” That will keep the brawls to a minimum once we return to pub quiz nights, but it doesn’t settle anything for sure.

Trivia offers the relief of certainty, a metric for correctness. There’s some guy (usually a guy) up there asking the questions, and he’s got a list of the answers. But those answers require a certain consensus.

By way of a chapter in Kathryn Schulz’s very good Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error, I ask my writing students to consider the nature of evidence. Schulz points to Descartes, Mr. “I think therefore I am” (“Cogito ergo sum.”) If they’ve thought about it at all, most students have a notion of Descartes’ famous phrase as some vague veneration of the life of the mind — “Thinking: like, that’s cool” — when it is the result of an exercise in radical doubt. It’s the only thing he can know for sure. He cannot be absolutely certain that other people exist. How do you know, for sure, reading this, that I am not a figment of your imagination? That the pixels on your screen — that the screen itself!— is not the result of some complex fantasy concocted by the chemicals in your brain. There is no external validation, no way to get out of your head and into another’s. The only thing Descartes could say with utter certainty was that there was an entity, an “I,” worrying over this question. That “I” is thinking about it; therefore that “I” exists.

What this has to do with trivia is … plenty? To work, a trivia contest requires some consensus about reality. The Warren Commission fingered Oswald. Mark it down. Trivia provides the comfort of certainty; it doesn’t necessarily get us closer to what happened.

At my first newspaper job, in Delaware, I filled in for my boss as a panelist in a 2002 Senate debate. In that campaign, Joe Biden was sleepwalking to his umpteenth term against some punching bag named Ray Clatworthy.

There were seven or eight of us, including the candidates, crammed into a cramped radio studio somewhere on the outskirts of Wilmington. Biden was playing the hits. He trotted out a hoary chestnut often used on both sides of the aisle, which Joe attributed to his “old friend Alan Simpson” who used to say “you’re entitled to your own opinion; you’re not entitled to your own facts.”

It’s a good line, especially for a politician — seemingly magnanimous, commonsensical, playing to the imagined average voter’s knee-jerk antipathy to “entitlements” of any kind. But in its folksy realism it ignores what may be the salient fact about the world and those of us (presumably) in it: that we have always entitled ourselves to our own facts.

This is the point Schulz makes, and that I’m at pains to relay to students: in some realms of public life — the law, the sciences, good journalism — there are contested-but-agreed-upon rules about what “counts” as evidence. You can “know” things outside the bounds of the evidence, but those things are excluded from formal consideration.

But in our day-to-day living and opinion-forming, no rules need apply. We rely on a small amount of observation and a large amount of inductive reasoning and/or taking other people’s word for it (we all do this, it’s how we get through the day). When some of those people no longer act in good faith — for whatever reasons — we get something along the lines of what Will Wilkinson outlined in passing in a post about D.C. statehood this week:

The success of authoritarian parties depends on unrelenting dishonesty and hyperbolic propaganda to delegitimize their political rivals, discredit reliable sources of information, and deceive their own followers. The main strategic advantage of consistent contempt for truth is that it allows authoritarian parties to bootstrap its supporters’ ordinary, initial partisan trust into a state of crippled judgment and epistemic dependency. This not only ensures that their supporters will not accept the truth about the party but will regard it as confirmation that those telling the truth are the real authoritarian purveyors of unrelentingly dishonest, hyperbolic propaganda.

Here’s a question: what does a QAnon quiz night look like? Are there questions about the specific effects of adrenochrome? About whether the Hillary Clinton we see in public these days a clone? About the outcome of her secretl trial? And speaking of JFK — is his son alive?

Wow. So. This got away from me a little bit. So if you’ll do me a favor let’s think of this not as a coherent argument, but a series of notes on questions I’ve been thinking about (NB: not those last QAnon questions). I would love to hear any reactions you might have to this, including of the GTFOH variety.

How Do You Finish A Book?

I have a lot of things I’m excited about for this department on the horizon, but for now, briefly two pieces on perseverance:

First, Jay Neugeboren’s Sixty Years of Tracking Publications… and Rejections, at LitHub:

The news has not always been as good as it’s been in my eighth and ninth decades. Before my first novel was published, I’d produced eight unpublished books. … Before I sold my first short story I’d had, by count, 576 rejections, and before I sold my first book, at the age of 27, close to 3,000 rejections.

(I believe that Neugeboren was the thesis adviser to my thesis adviser, Doug Whynott, way back when. Doug, if you’re out there, is that right?)

Second, from The Millions, Michael Bourne’s The Failure Artist: Writing Bullshit, Getting Rejected, and Keeping At It:

If you’re a writer not spoiled by genius, you’ve had a few of these moments: You’re cruising along, seeing your book through the eyes of your characters, and then one day, the lens shifts so you can view your work through a potential reader’s eyes—and what you see is what total shit you’ve written.

Coda: I lost on Jeopardy!

And yes, those of you who know me and have read this far have, I can only imagine in a letter about trivia, been expecting me to mention Jeopardy!

Way back when, in the spring of my freshman year at Penn (that’s 1998, if you’re scoring at home), I found myself on the stage at UC-Berkeley’s Zellerbach Auditorium for that year’s College Jeopardy! tournament. I lost in just about the worst way.

I acquitted myself pretty well for the first two rounds. If you’re interested in the stats: I found two Daily Doubles, missed one and hit one, bet too conservatively on both. I correctly answered a pretty good share of the questions (or questioned a pretty good share of the answers) that I buzzed in on (19 of 23, but who’s counting?).

Heading into Final Jeopardy I was in second place, with $3,900, behind Mary Washington College’s Kristen, who had $6,500, but in front of USC’s Leslie ($1,800)3. The wagering was easy. My only hope was to bet everything and hope that Kristen slipped up, or that I could get my score high enough to make one of the wild card slots to get to the second round. The category was “Quotations.”

Alex Trebek read the answer: “In 1883 he wrote, ‘Your true pilot cares nothing about anything on Earth but the river.’”

OK.

OK.

OK!

Look: you know it’s “Mark Twain.” I know it’s “Mark Twain.” I knew it then. You’d better believe I know it some 23 years later.

But, put yourself in my poor, sweet, innocent, stupid shoes those decades ago: would the universe lay this sort of gift at my feet? Isn’t it too obvious? The river, really? What are the odds that a kid from Missouri would be handed the Missouri icon on Final Jeopardy!?

I overthought it. Worried that my first instinct was too obvious, I said Emerson. Emerson, I thought, not having read him, could have said something like this in 1883.

Emerson died in 1882.

Kristen put Twain, Leslie and I missed it. That was the end of my Jeopardy! run.

As we watched the episode in the dorm’s common room several weeks later, my friends were pretty forgiving. I’d gotten The Simpsons question right — missing that would have been embarrassing.

Home from school that summer, the reaction was different. My performance was much-discussed.

“Hey Sebastian! Phyllis and I are wondering when you’re gonna be on Millionaire!” This was Loren, Dad’s neighbor up the road who’d taken over as janitor at my old elementary school. In a lower, more confiding register, he said “Y’know, I said to Phyllis, ‘I think it’s Mark Twain. He’s gonna get it.’”

Others were even more forthright. One afternoon I accompanied my father to one of his preferred watering holes. At the bar was the late Bill Grace, Dad’s colleague, office mate, and drinking buddy.

“Hey Sebastian,” Bill said as we bellied up. “When are you going to Hannibal?”

I blinked.

“Hannibal?”

“Yeah,” Bill said. “So you can find out who the fuck Mark Twain is.”

“Congratulations” to Brian, who finished fourth in our Rundle, and will move to Rundle B, next season. I’ll be in Rundle C, with Eric and his brother, Scott.

For the record, I was right: 1850-1853.

I am compelled to assert here that the totals are low because they were two difficult rounds.