Welcome to … <pulls spiral-bound planner out of jacket pocket; furiously shuffles pages> March!?!?! How’d that happen?

For my part, the semester happened, and I haven’t been able to catch my breath until now, and that’s because … it’s Spring Break, which is why I write to you from beautiful Montego Bay, Jamaica.1

—

Two months ago, right before the semester, my dad and his wife came out to visit. My father is an economist; his wife has a J.D. They both teach at a small college in Missouri. I told them I was putting the finishing touches on the syllabus for a new course, Creative Nonfiction.

“Now, this might be a dumb question, but what is creative nonfiction?” Dad asked.

Friends, if I weren’t the self-possessed 43-year-old that I am today, I might have suffered a fatal ego-wound, folding myself into a paper airplane of resentment over the fact that even though my graduate degree says “creative nonfiction” on it, the old man appeared to be encountering those words together for the first time.

But say this for 20 years of therapy, plus 20 years and 1,400 miles of physical separation: it tempers the always-fraught parent-child interaction. I managed to avoid my initial instinct: to reply with something cutting like “Oh, it’s where you assemble a bunch of facts to make up a story about why something happened — just like economics.” Instead, I granted that the question Dad posed was a very live one indeed and, in fact, adopted that question — “What is creative nonfiction?” — as the course’s central preoccupation.

God, I’m well-adjusted.

—

Anyway, the plainest answer is that “creative nonfiction” is a genre label that admits an impressive number of prose specimens into its big tent. In other words, “creative nonfiction” has a lot of a.k.a.s: essay, memoir, narrative essay, lyric essay, literary journalism, narrative nonfiction, documentary writing, New Journalism, graphic memoir … The list can go on and on, depending.

But that list of Things Creative Nonfiction Might Also Be Called doesn’t address the Dad’s implication, the question beneath the question: isn’t “creative nonfiction” a contradiction in terms? After all, if something is “nonfiction” that means — and, stay with me here — that it is not fiction, i.e. not something the writer made up.

If you’re not making stuff up, whence the creativity?

Or, as William Gass put it: “Why is it so exciting to say I was born. … I was born. … I was born? I pooped in my pants. I was betrayed. I made straight As.”

To answer Dad: it’s “creative” because representation of some aspect of the world in prose requires selection — of detail, event, emphasis. You have to decide, pace Bob Seger, “what to leave in, what to leave out.”

Example: you want to describe your room. Among the things you might include in the description: the aquarium that’s been empty since your dog ate the turtle, the steak knife you stuck in the wall to hang your coat from2, and the lucky rock you keep by your monitor. Each available option — including all three details, or none, or one, or some combination of two — will give the reader a different impression of who this “you” character is and what that character might do.

“Why is it so exciting to say I was born. … I was born. … I was born? I pooped in my pants. I was betrayed. I made straight As.”

To answer Gass: It’s exciting because, in confronting these choices — some weightier than the ones in my example, others more trivial — you will invariably surprise yourself. In choosing, we are quite literally figuring out what we think, what our values are (at least what we thought and what our values were are at the moment of writing).

As graphic memoirist Alison Bechdel told my Northeastern colleague, Professor Hilary Chute, in a talk at Harvard recently: “The main thing I love about memoirs is the challenge of finding a coherent story in the random events of life … You can’t make anything up. So much of writing for me is … figuring out how to sequence things, how to figure out what comes next in the story or argument. And I find that it’s only by engaging in that process that I learn what the story’s about or what I’m trying to say.”

My first mentor in nonfiction writing was a long-time feature writer for the Washington Post, and his lodestar was James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. In 1936, Agee and photographer Walker Evans went to Alabama for Fortune Magazine to write about sharecropping families. Agee was wracked with guilt over what we would now call his privilege and the impossibility of doing justice, in a mere magazine article, to the immiseration he found there. Fortune rejected his 7,000-word first attempt. He spent the next several years revising and rewriting his story of “Three Tenant Families” into a 400-page book. Agee’s stated goal — he put it right there in the text — was to capture “the cruel radiance of what is.”

The impossibility of that project is what gives the book its majesty and makes it an inevitable failure. There’s a line that I love for its earnestness and unintended comedy: “I shall not fully describe the contents of the bureau drawers.” This is the opening sentence of a paragraph that takes up about a third of the page and in which Agee … describes most of the contents of the bureau drawers. Such was his commitment to that “cruel radiance” he felt compelled to admit at the outset he was leaving some items out.

Agee wanted to build an edifice to contain the world — or at least contain completely some corner of it. Most of today’s nonfictionists know that’s impossible, because any retelling of “what really happened” much less “what it was like when it did” must rely on the memories of the participants and their necessarily partial (in two senses: both incomplete and interested) accounts.

As a former newspaper reporter, I am a recovering member of the obsessive “what really happened?” school. I’ve been swayed by, among others, the late Janet Malcolm, about whom I’ve recently written and podcasted and will not belabor here except to say she saw her job as one of mediating among those competing accounts.

Add to the problem of self-interest the further complication of memory. David Shields, in Reality Hunger: A Manifesto — a fascinating work of appropriation, plagiarism, and provocation — maintains that “Anything processed by memory is fiction.”

In last year’s Artful Truths: The Philosophy of Memoir, Wellesley professor Helena de Bres, considers the argument that because there’s “no such thing as a unified and stable self,” and because “memoirists aim, apparently, to tell the story of such a self, their story can’t possibly be true.” She rejects this claim, arguing that whether or not there’s “really” a self, there is at least a “psychologically constructed entity: a thing that exists and has real consequences but that is ultimately, subjective, mind-dependent.” (Other things that fall into this category: “state laws, nations, colleges, and marriages.”)

So one way to think about creative nonfiction is as an attempt to describe not just what happened, but what it felt like. (Memoirist Mary Karr: “The problem is not that your mother hit you on the head with a brick; the problem is that you love her.”) Tobias Wolff, in the preface to his bestselling memoir This Boy’s Life, notes that he “has been corrected on some points” but also that he’s “allowed some of these points to stand, because this is a book of memory, and memory has its own story to tell. But I have done my best to make it a truthful story.”

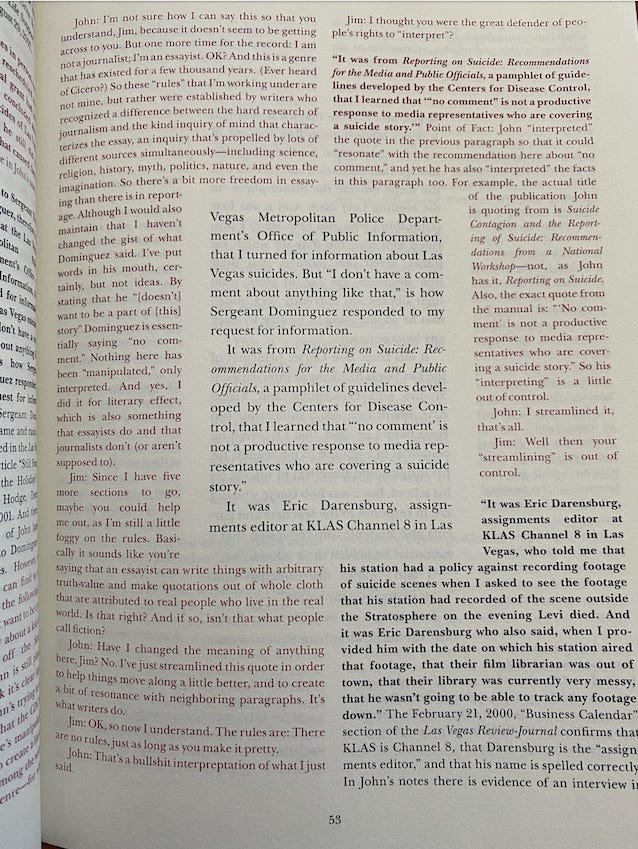

“Memory has its own story to tell” sounds like a softened version of Shields’ “memory is fiction.” Shields and others treat this as an argument to offer little more than a bemused shrug at the line between “this happened” and “this didn’t happen.” John D’Agata, whom The New Yorker’s James Wood has called “the renovator-in-chief” of has argued, loudly and at length, that nonfiction shouldn’t let a niggling focus on facts stand in the way of truth. To make his point, he published The Lifespan of a Fact along with his fact-checker and foil, Jim Fingal, in which they stage (as the flap copy has it) “a penetrating conversation about whether it is appropriate for a writer to substitute” “truth” for “accuracy.” The pages look cool, anyway:

Some of these would-be Talmudic disputes come down to things like whether D’Agata should be able to change the number of Las Vegas’s licensed strip clubs “because the rhythm of ‘thirty-four’ works better in that sentence than the rhythm of ‘thirty-one.’” This is of course a deliberate provocation on D’Agata’s part. In changing a truly unimportant detail in order to draw attention to our obsession with verifiability, he is self-consciously pushing at the boundaries of the genre. Godspeed to him, I can’t venture quite that far afield.

I could go on, I’m sure I will go on. As part of a new occasional series for, let’s call it, A Saturday Letter, Volume II, I will be reading my way through the New York Times’ 2019 list of The 50 Best Memoirs of the Last 50 Years. Like any best-of list, it’s arbitrary and not actually definitive, but there’s lots of interest in there, and it will be a useful structure as I (and my class) continue to think out loud about truth, accuracy, and the sheer impossibility of pinning down what actually happened.

For now, though, I’ll leave you with this caveat lector from Elena Passarello, who considers these issues at length on I’ll Find Myself When I’m Dead: A Podcast About the Literary Essay, with her co-host Justin St. Germain:

“Nobody wants to be duped,” Passarello said in this episode. “And I think the only way that people can stop feeling duped is if people understand that they’re always being duped.”

“Montego Bay, Jamaica” should be read as “inputting numbers into TurboTax while drinking from a coffee cup with a tiny umbrella in it.”

This person knows who they are.

So good to read a new Letter! Love it, Sebastian. And Bechdel nails it.

Which of the things you say here are features of creative non-fiction are not also features of uncreative (?) non-fiction (A1 newspaper stories etc)? They also rely on memory, are selective in what the report, etc.